The terrifying state of college students

Despite support for free speech in theory, many of America’s current undergraduates don’t support it in practice

It is often said that education is the slow transmission of civilization from one generation to the next. What we’ve seen on many American campuses in the past two decades is something closer to the opposite: a dismantling of that inheritance in favor of an illiberal ideological project. This should concern thoughtful liberals and conservatives alike.

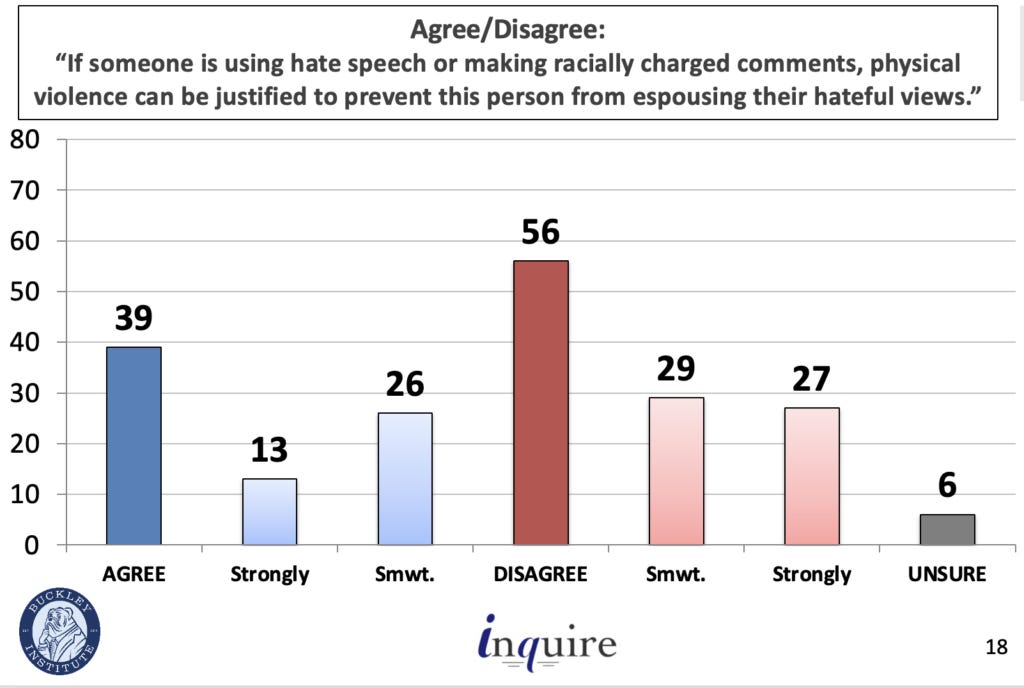

The Buckley Institute’s new national undergraduate survey presents some chilling results. On one level, students profess admiration for the Constitution and the First Amendment. 73% say the Constitution is important, 90% say the First Amendment matters, and a record 60% even recognize hateful speech is still legally protected. Yet in practice nearly half think it’s appropriate to shout down invited speakers, and almost 4 in 10 believe violence is justified to stop “hate speech.” One-third say offensive speech should be criminalized. This represents a fundamental rejection of the habits of a free society. The survey results should absolutely concern you, as one day these students will be in positions of power or at least working alongside you. We’ve already seen the results recently, as adult society is still rebuilding an immune system against the destructive nature of extremist ideals (we just went through this).

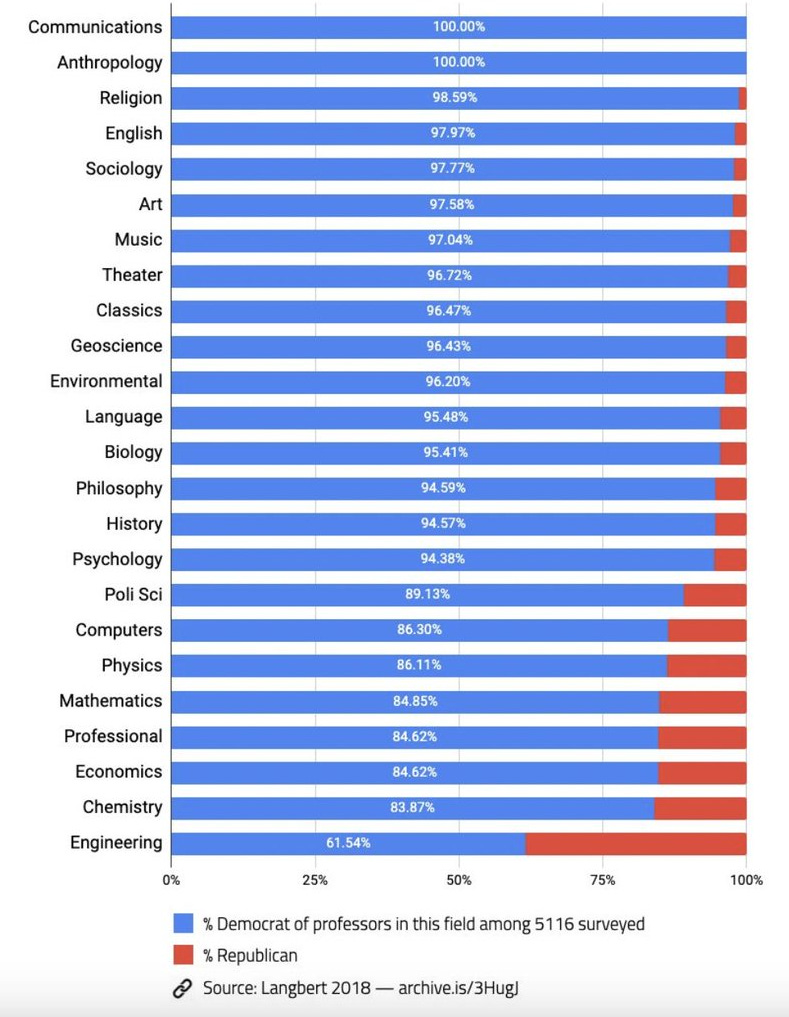

That contradiction of free speech in theory, repression in practice is not an accident. It reflects what students are actually taught by many professors. For years now, the campus has served as the incubator for a new civic religion. Its sacred texts are grievance studies and its catechism is the oppressor–oppressed binary derived from Marxist thought. Students learn not that debate is a process by which we approach truth, but that certain views are so intrinsically harmful that they must be suppressed. And when you see opponents not as fellow citizens in error but as heretics, you don’t reason with them, you try to silence them. The survey’s finding that more than half of students say they’ve felt intimidated expressing ideas different from a professor’s is what you’d expect in such a climate. Doesn’t sound very liberal to me.

At least part of the reason this ideological capture has persisted is what’s missing from the curriculum. If one reads a typical college or even high school history syllabus today, the great villainies of the twentieth century appear to be almost exclusively Nazi. Of course the Holocaust deserves central attention, it was a singularly unique kind of evil. But even as a Jew, I recognize that wasn’t the only horror. It makes no sense we ignore the other recent totalitarian catastrophes of communist regimes in the Soviet Union, Maoist China, Cambodia, North Korea — these collectively killed more than 100 million people. This scale of human suffering is often treated as a footnote, if mentioned at all. Students may graduate knowing the details of D-Day but almost nothing of the Holodomor or the Khmer Rouge. That imbalance has consequences.

The survey’s economic findings reveal the outcome of that historical amnesia. While capitalism still narrowly outpolls socialism at 40 to 36 percent, 46 percent of students say that countries like Cuba and the Soviet Union (dear lord) offer a better economic model than capitalist nations such as the United States. What these kids actually want is a better safety net, but instead they would get a system which produces chronic shortages, stagnation, and mass poverty. The romance of socialism thrives in classrooms where the failures of collectivist economics are treated as aberrations rather than the predictable results of central planning. It is telling that many also favor government-run interventions in housing markets and flirt with the idea that state-run grocery stores would be fairer than private ones (which are some of the least profitable businesses that exist - grocery store margins are roughly 1-3%). A generation that has been encouraged to see markets as inherently unjust is naturally more receptive to such proposals, despite their consistent failure in practice.

The result of all this is cohorts of college educated students primed to see liberal democracy as a rigged system and to flirt with ideas that, whenever tried at scale, have produced not utopia but famine, secret police, and gulags. The language has changed, where today’s radicals talk of “equity” rather than class struggle, but the underlying worldview is the same: society is a zero-sum battle between oppressors and oppressed, and justice requires that power be seized and redistributed. That way of thinking corrodes the very conditions of a pluralistic republic: freedom of conscience, the presumption of good faith, the willingness to engage those who might hold different viewpoints. This all produces an inability to negotiate a middle ground between parties, let alone hold any classical American values.

Again, we know this danger is never sequestered to the ivory tower. As today’s students move into journalism, corporate management, and eventually government, they carry with them a posture of moral absolutism that leaves little room for compromise or genuine civic friendship. The reason why is many professors are not actually liberal, they are radicals (or just full of luxury beliefs) and reject American liberalism in favor of something else.

A society cannot endure long when large numbers believe that political disagreement justifies violence or that economic experiments that fail every time deserve another try. We all suffer when we repeat the mistakes of the past and historical amnesia takes hold. A better civic education would inoculate against this, by teaching not only the ideals of the American founding, but also the hard-won historical knowledge of what happens when those ideals are abandoned.

Okay, just thinking through this real quick. On one hand, I think you're playing into the old trope of pointing to the extremities as proof of a larger consensus. That is, you're taking the most extremes and are suggesting they are the norms.

For example, a third saying hate speech should be criminalized or that violence is acceptable to stop hate is an extreme — it's also far from the mean. (One thing I take exception to is the suggestion that shouting down invited speaker is inherently wrong: it's an expression of free speech itself and the free speech rights of the first speaker don't override those of anyone else.)

Here's an exceptionally good essay from someone I hold in high regard on the issues confronting "free speech culture." I think you'd find what they have to say interesting: https://www.popehat.com/p/how-free-speech-culture-is-killing-free-speech-part-one

For your third paragraph — and I cannot emphasize this enough — every. single. word. applies to Hillsdale College as well. This unwillingness to grapple with difficult conversations is not something born out of Marxism, but is likely more to do with tribalism and power dynamics.

Fully agreed with fourth graph.

Agreed with fifth graph with the addendum that: well, they're not wrong. Markets and our system of government *have* failed to provide a safety net. That they're open to a system that isn't great and has a long history of failure and oppression isn't ideal, but at a quick glance I'd say it's not much different than what we have now.

I'm not sure the sixth graph follows out of "we don't like hate speech." I also suspect the first sentence is an extension of taking the extremes as norms.

Seventh graph: I mean, I think that's just trying to damn all of society, man. I also think it's a caricature of higher education.

Completely agreed on last graph.

I don't think we can be surprised that a bunch of young people, whose future prospects for owning homes, having kids, and living normal comfortable lives have been fucked by greedmongers and the people who enable them, are amenable to a system and at least purports to be more just economically. I own a home and live a pretty great life, but watching as criminal fiance people get constantly get bailed out by the taxpayers (as opposed to home owners who were given predatory loans by those same finance people) really takes a toll on one's belief in capitalism. Even if the version of it we have isn't the best, it's still what's being sold as the justification for exploiting people and resources just to make a buck.

Communist systems are grossly inefficient and it's also worth noting that all the major communist/socialist figures died very rich men, so I'm not sure socialism is as different from capitalism in terms of result as people want to believe. There are winners and losers, but I can understand why young people would gravitate to that believing that at least they might have a better chance of being one of the winners.