Two concepts central to behavioral psychology the top 1% of creators have mastered

Smash that like button, hit that subscribe, tag that re-share (none of this actually helps for getting ideas shared, today we'll explore 2 key concepts that will: classical and operant conditioning)

Quick note: your users are not mere farm animals to be trained, and you can’t force anyone to share ideas online. We’re not going to describe any manipulative or black hat tactics today (we typically go to great lengths to debunk such methods and share how they actually work against you). But I do think understanding the basic psychological concept of conditioning is an important one for marketers and creators of all variety. It’s more powerful than gaming algorithms or finding cheap, short-term exploits. With that disclaimer out of the way, let’s proceed…

The subhead of this story was poking fun at my YouTube friends, hopefully at least some of this audience got the joke. Here’s a fun (it’s 18 seconds, play it, just trust me) illustration by voice actor SungWon Cho on the ongoing phenomenon most of us know well (if you don’t watch enough YouTube to get this I’m surprised you’re reading this Substack, which spends entirely too much time on nerdy/internet-insidery things).

Anyway, asking people to smash that like or re-share is mostly a pyrrhic effort and an exercise in spinning your wheels at best and annoying users at worst. We’ve had 3 decades of using the internet and by now know when we find something worth sharing and that we are in fact able to share it with our networks, lists or internally with teams. But how do you best persuade such all important power users (we’ll bucket everyone who shares links online in that category for this exercise, large #’s aren’t what matter anyhow) to care about and share your hard work with recurrence ? Let’s explore this today in brief.

We must begin by understanding which users regularly and reliably share/curate

A prompt from the creator is in all likelihood unnecessary, and in fact can be seen as thirsty especially to the percent of internet users who are “sneezers.” What is a sneezer? As Seth Godin described years ago in his popular marketing book, Purple Cow [abridged, emphasis mine]:

Sneezers are the key spreading agents of an idea. These are the experts who tell all their colleagues or friends or admirers about a new product or service on which they are a perceived authority. Sneezers are the ones who launch and maintain ideas. Innovators or early adopters may be the first to buy your product, but if they’re not sneezers as well, they won’t spread your idea. Every market has a few sneezers. They’re often the early adopters, but not always. Finding and seducing these sneezers is the essential step in spreading ideas. Sneezers love to sneeze. Sneezers are quick to tell their friends, sell their friends, even drag their friends to a store.

When it comes to influence online, it’s for sure made up of a pareto distribution with sneezers at the important end. Highly unequal, where we may assume, at the very least, 20% of users account for 80% of shares. It might even be higher if Jacob Neilson is to be a guide with his participation inequality thesis, wherein early social web research suggested closer to 10% of web users are responsible for nearly all original content and sharing/curation with 90% purely lurking. Of course, things have evolved since then and more are participants, but still the vast majority will always simply lurk. While technology changes, human behavior, especially comfort in the public sphere, mostly remains the same.

Why do we share what we do? Let’s explore 2 concepts central to behavioral psychology to better understand

To the point of today’s post, I want to talk about two psychological concepts: classical and operant conditioning.

Stimulus-response theories are central to the principles of conditioning both classical and operant which we’ll summarize below. They are based on the assumption human behavior is learned. One of the early contributors to this concept, American psychologist Edward L. Thorndike, postulated the Law of Effect, which stated that those behavioral responses that were most closely followed by a satisfactory result were most likely to become established patterns and to reoccur in response to the same stimulus. We’re going to focus exclusively on encouraging positive associations and patterns with the aim of conditioning users to share more of your work, without even asking them.

Because, we want to do everything we can to get our most connected users to be our advocates. And before we proceed, let’s be clear: this is not in any way, shape or form a type of “growth hacking” which I’ve written on repeatedly as essentially a form of webspam and manipulation, something we would never recommend. Quite the opposite, to succeed here requires focused effort and taking shortcuts as we’ll show actually may well kill any chance you have at success. Also of note, I do not believe any successful creators consciously consider they’re doing this. And that’s kind of the point, because they are so passionate about what they do it’s infectious and so sharing is an organic, almost unconscious byproduct. But one of the main points of my Substack is to help us understand human behavior applied to marketing, and so analysis behind the why of what separates the “haves” from the “have nots” of online attention is a worthwhile exercise we believe is important to spend time on.

Let’s next define the two major types of conditioning: classical and operant, both of which have application for all of us whether we realize it not.

Classical conditioning (also called Pavlovian or respondent conditioning)

Let’s start with digging into classical conditioning, sometimes also called Pavlovian or respondent conditioning. Everyone knows the story of Pavlov’s dog. A summary for those who slept through 7th grade science class:

The original and most famous ex of classical conditioning involved salivary conditioning of Pavlov’s dogs. During research on the physiology of digestion in dogs, Pavlov noticed that, rather than simply salivating in the presence of meat powder (an innate response to food that he called the unconditioned response), the dogs began to salivate in the presence of the lab technician who normally fed them. From this observation he predicted that, if a particular stimulus in the dog’s surroundings were present when the dog was presented with meat powder, then this stimulus would become associated with food and cause salivation on its own. In his initial experiment, Pavlov used a metronome to call the dogs to their food and, after a few repetitions, the dogs started to salivate in response to the metronome. Thus, a neutral stimulus (metronome) became a conditioned stimulus as a result of consistent pairing with the unconditioned stimulus (US – meat powder in this example). Pavlov referred to this relationship as a conditional reflex (now called Conditioned Response).

Applying this to digital publishing – of any variety – if you become known for a high degree of signal for a long enough stretch of time, the mere act of publishing will be enough for people to, as soon as they see you’ve run something new, have an autonomic reaction to consider sharing it. Without even requiring a prompt, as the subheading of this post poked fun at. Now, your readers are hardly dogs – but Pavlovian reactions, or conditioned responses are a powerful force that we humans are just as receptive to as any other animal (we are indeed animals too, after all!). It’s why popular creators get more popular, people can’t help but share them. They know work quality is going to be high and know sharing means they’ll receive engagement (which triggers its own, separate rewards). And with so many curators (there are far more curators than original creators) it’s something of a landgrab to be first, or at least early, to share something new/novel. It’s the same reason memes get stolen/copied with such zeal and speed. The social web overvalues what’s new, now. It’s a huge miss to not take advantage of this.

Your goal as a brand, creator or consultant should be to use this type of conditioning to your advantage but also go beyond it, as the internet being an interactive medium lets you engage directly too (in addition to simpler act of ‘ringing the bell’ or in this case, hitting publish). This moves us into operant conditioning, which is equally simple to understand and perhaps even more practical for our purposes.

Operant conditioning (also called instrumental conditioning)

Classical conditioning process involves pairing a previously neutral stimulus (such as the sound of a bell or the publishing of an idea) with an unconditioned stimulus (the taste of food or sharing with your social networks) as we reviewed above. Thanks to classical conditioning, you might have developed the habit of going to the kitchen or your nearest café for a coffee every time a Dunkin Donuts pre-roll ad comes on while watching YouTube.

Operant conditioning (also called instrumental) focuses on using either reinforcement or punishment to increase or decrease a behavior. Through this process, an association is formed between the behavior and the consequences of that behavior. Let’s consider an example with positive reinforcement (we won’t be recommending you use any sort of negative reinforcement at all here, as we can’t imagine how there would be a productive application).

During practice for your office baseball team, your coach yells, "Great job!" after you throw a solid pitch. Because of this, you're more likely to pitch the ball that specific way again. This is an example of positive reinforcement.

Another ex is while at work, you exceed your manager's performance expectations for the month, so you receive a bonus in addition to your usual paycheck. This makes it more likely that you will try to exceed the minimum sales quota again next month.

How might you accomplish this as a creator? You could use some of the proven tactics of digitally savvy companies for your own efforts. An easy example would be simply monitoring social media channels for when people share or respond to your work, and re-share their thoughts directly to your community, or just respond to thank them for taking the time to post a link and that you greatly appreciate the support and encouragement (either privately or publicly). This succeeds in helping connect further with that reader/fan and lets them know you appreciate their unique thoughts/endorsement. Validating people like this is an incredibly powerful thing, because think of how little we get it in life. It’s so incredibly rare. As a note, it’s also powerful when you re-share someone who disagrees with you. You’re showing you appreciate ideas from all perspectives. It shows confidence, which is attractive.

There are many more sophisticated things you can do (some go so far as to send swag to fans - just always make it personal for best results). A fun, simple meta-example here is Substack sent me a canvas bag, branded mug and personalized note as I frequently extoll virtues of their platform on various public social channels and to individuals directly. I already organically share their news and other newsletters and am fairly conditioned here already so they didn’t need to do this, but it serves as a fun marketing example.

Anyway, the unconditioned and conditioned response of subscribers is when you publish, they’ll read your work. In other words, it’s natural after people sign up for something that they’ll consume it – that’s why they subscribed. But, merely reading is not enough if you want to grow. You need to develop a conditioned response in users to share what you’re doing with their networks. The paradox here is this isn’t something you can accomplish directly by asking (nor should you try this way, for reasons I mentioned above).

This is becoming even more important for growth in increasingly saturated (content) markets. I’ll show you a quick example why – popular writer Matt Thompson got to a point many other users have reached [emphasis mine]:

Here’s what I’ve come to realize about myself: I fully accept that there’s not a particular link in that ridiculous heap that will change my life. It’s been a while since I worried about missing a single killer post or app or XKCD or whatever; if it’s valuable enough, it’ll find me.

All the more reason to “become a beacon” on the digital landscape and ensure you are lighting the way and not lost in an infinite sea. But Matt has a point, and it’s this: there is a bloat of ideas among us from companies, media and individuals all fighting for our attention and the truth is many users, instead of meticulously catching up on email subscriptions, YouTube channels or Twitter feeds, will entrust the discovery of what they consume to the wisdom of their peers and/or the crowds via social streams. And, as more people do this, the value in having an audience motivated to share, link and bookmark your stuff goes up beyond merely having piles of passive subscribers (they matter too, of course, they make up the majority of the web, but for today’s post we’re talking about the active ones).

Back to the example of Pavlov, your goal should be to condition subscribers to share your work as a natural response to your publishing.

There’s a simple formula to getting there: only publish that which your core readers are interested in sharing. Sounds simple? It isn’t. It requires editing yourself. Ruthlessly. As it’s ultimately what you don’t publish that defines your brand. The neat thing is, you can measure this and understand what concepts work best. Do this long enough and subscribers will, to the extent possible, become conditioned to share what you post as an natural reaction. Of course, people who share ideas on the web with frequency are also discerning so it’s unlikely they’ll share everything (and that’s just fine) but you certainly could optimize for this dimension if you wanted. Note: I personally don’t do this here as I bias to simply being myself and am not trying to hit any specific #’s with this site (when employed and at company, which I currently am not, that’s a different story, marketers live and die by analytics). But as strategist I want to share all potential paths so we’re at least aware of what is in our toolkits, even if we elect not to use it for every project.

At many popular destinations users are conditioned to share first, consume second

Obviously the web’s top destinations share ideas that meet strong minimum levels of quality, but what’s even more interesting with these examples in particular is the fact that people race to share the material before they’ve even finished reading/viewing it (it is normal occurrence to see Tweets that say “listening to a great podcast, check it out here” or witness weekly race to be first to submit XKCD - one of the web’s most popular webcomics, the author of which makes a full time living from - to Reddit merely because it’s new). Twitter and other social sites know this behavior is real, and even have gone so far as to add features prompting users “would you like to read this article before sharing it.”

In these cases (and others) audiences have been conditioned to share, thus helping attract new audiences and cutting through the noise of cluttered feeds and inboxes.

XKCD rose to prominence publishing every Monday, Wednesday and Friday but perhaps even more important than publishing on a timed schedule, is the signal to noise ratio. For core fans/subscribers – the ones who actively share material – everything published is viewed as signal. People share their stuff because they know that what the quality will be even before clicking. They also deliver what they know their fans want, meeting that expectation again and again and building a powerful feedback loop.

The web has fostered and encouraged a culture of sharing, and by consistently creating material that taps into the reasons why we do so, your readers will become conditioned to share what you create. There are so many social sites now and even more users actively looking for steady streams of ideas they can use to grow their own strength on those sites. If you have an audience, you for sure already have at least some of the right users to tap into this today, it’s a safe bet some % of your subscribers are already “sneezers” as described above.

You need a decent subscriber base before any of this works

Subscribers are the bread and butter of popular destinations, and without a decent base you don’t have enough of a base to create repeated sharing of ideas. Organizations (and individuals) with audiences win and have a daily and durable advantage. Only a small % will pass on, and while you don’t need millions of subscribers it definitely helps to get at least a few hundred, or better yet thousand engaged users. Sure, you can draw traffic from search engines etc too, but those users likely won’t share anything. Your subscriber base is made up of the people who hang on your every word and already look to you as a trusted source. You already converted them. They’re your “vital visitors” as I like to say. Years spent looking at analytics has shown this to be true for me in nearly all cases. They’re the ones who, for every successful brand, become conditioned to share as they not only desire and look forward to your thoughts, but they’ll in time trust you and find enough value in it to share with their networks.

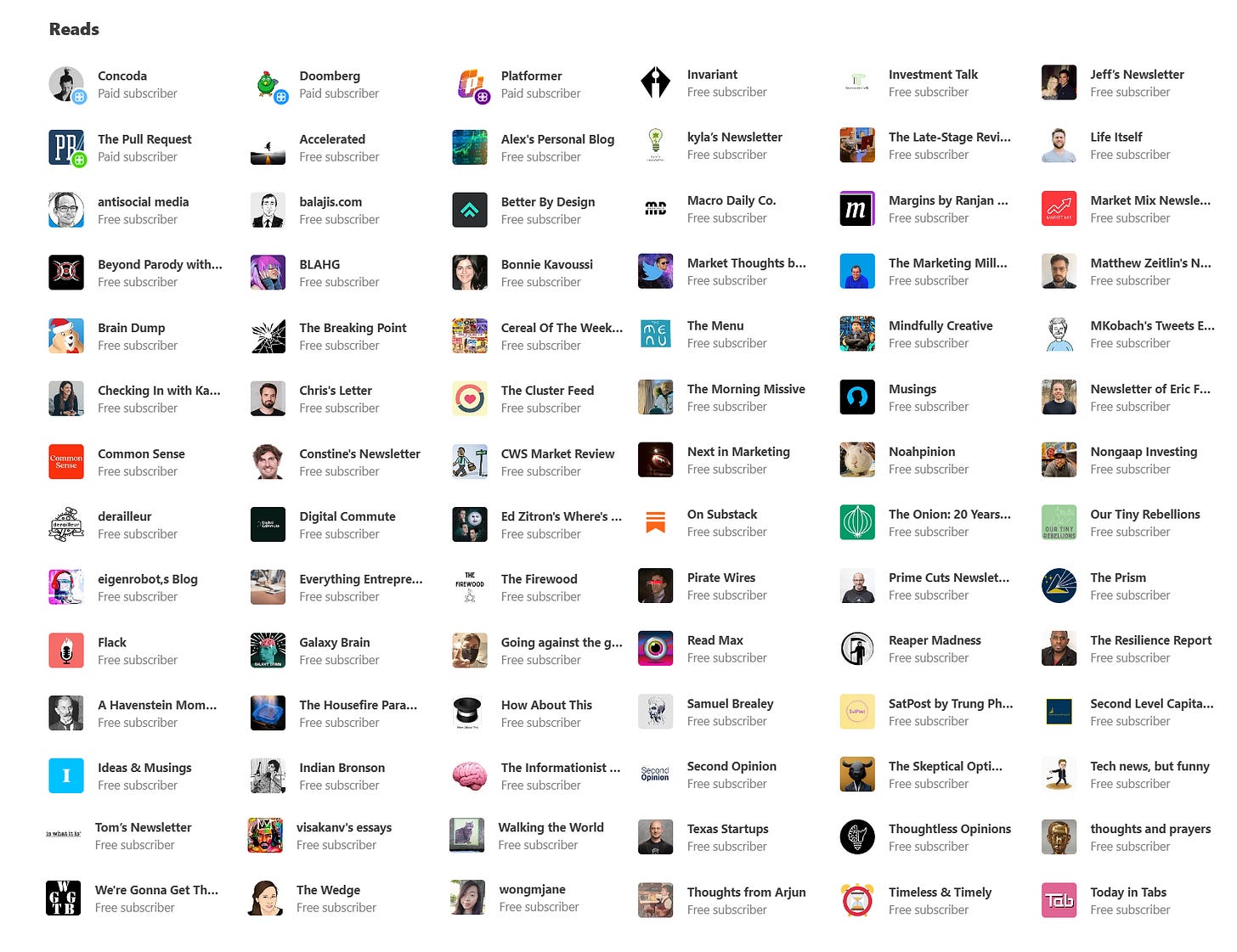

I think about the sites I’m subscribed to that provide me great ideas daily – and it’s filled with ones that are so good I just have to add them to my (growing) subscriber list and frequently share with my social followings. Below is a listing of all the newsletters I subscribe to on Substack, all of which I’m happy to recommend (linked here - note Substack profiles are an untapped goldmine to find new publications to follow).

Some very basic popular archetypes of ideas we share

If you’re already a sophisticated digital publisher or company, you can skip this part of the post and go right to the end. This final bit won’t be anything new for you. For everyone else, understanding a bit on what we’re motivated to share is the final topic I want to review briefly. The Internet is the great enabler for spreading ideas, it’s as close to pure information meritocracy as we’re going to get on Earth. And the modern state of the web offers an extremely diverse array of tools to share anything we want with communities, friends, family, co-workers or even complete strangers.

Bloggers, reporters, marketers, artists and pretty much everyone with good ideas wants to share them with people, and then ideally those people will share the idea with their connections. This will hopefully continue to the point where your work picks up steam to reach several concentric circles out.

I’m not going to go into specifically how to make ideas that spread. Instead I’d like to share a few basic archetypes of what kind of ideas get shared. This might help spur your next big idea, but I’ll leave the creative work to you, as only you most intimately know your audience and style. Satisfying some core tenants (don’t be afraid to use multiple at once) will help create a situation your community is primed/conditioned for sharing more consistently.

It’s absolutely hilarious or whimsical for insiders or a given tribe

Let’s be honest, the majority of people online love humor, memes, and things that make them smile. And, the influencers of the web especially love clever humor. I am probably forwarded more ‘funny’ links than anything else by friends and family, my casual connections even professional colleagues. But generally, it needs to appeal to a specific subset of people, as more broad humor we might not know who to share with, specifically. If you’re the rare person funny enough to get people to blast to everyone, more power to you.

It’s incredible or unbelievable in a novel way

Sometimes ideas that must be shared is just so incredibly mind-blowing we can’t help but submit it to a social network or email it to a friend. It becomes a must share piece when it completely changes our worldview on something, or gives insight into something we had no idea existed. Novelty sells, we’re hardwired for it.

It’s deeply emotional

Even though the Internet is not as personal as face to face communication, plenty of ideas on the web evoke deep emotions from us – both positively or negatively. Either way, it is basic human nature to want to share in deep emotional experiences, and is a strong reason why people share. If it impacted your mood, it’s reasonable to think it can others. Hopefully we think more critically about this and nudge the world in a more positive direction, we actually have some power here collectively.

It agrees with our worldview and confirms existing biases

We all have sets of friends who share similar interests and opinions. When something is strongly geared to agree with a certain worldview, people love to share it to continue to spread that view with their contacts and reinforce/confirm beliefs.

It makes us stop and think

Some ideas are so deeply thought provoking, they cause us to pause what we’re doing for a minute and really think about existence, our work, or family, a philosophical or religious concept and what it all really means. If it is successful at this, we definitely will want to share that experience.

It isn’t covered by mainstream media

Stories and ideas not generally covered by the mainstream media have a way of being shared amongst all users of the web, not just the Twitterati or trending on TikTok/Reddit. Small, obscure stories are beautiful. You’d be surprised how many email links to friends of obscure blog posts or politically controversial ideas big media ignores. There is definitely a feeling that the web’s users, for the most part, are seeking what is new, novel and offbeat. The types of stories you haven’t heard of are far more likely to spread than regurgitated stuff.

It’s worth a smile

A huge reason people love to share is because they know it will make the person or industry they’re sharing it with smile. It’s as simple as that.

It’s dramatic

Our culture loves a good drama, and something with high levels of drama is certainly going to be shared by people. Especially on the web and especially lately, people thrive on controversy, as long as it isn’t happening to them and they can sit on the sidelines and comment.

Mass-scale embarrassment

Similar to the dramatic, for some reason people love to share things are embarrassing to someone on a mass scale. Miss Teen South Carolina is a perfect example. I don’t personally understand appeal on this one, but it’s certainly an archetype.

It’s provocative (but SFW)

Users love sharing videos that are a little risqué, for ex, but are still kosher to watch at work or with others in the room. People generally are not quick to share things that are inappropriate to be opened up as many view links at work. I can’t believe this needs repeating, but it definitely does.

Next time you forward something to a friend or post it to a social network, think of the underlying motivation for why you wanted to share it. Were you conditioned to by that brand or story archetype already? How? Does your work evoke similar strong for your readers? Important questions to spend time thinking on.

Wrapping up…

Hopefully this helps put you on a journey to increasing organic, word of mouth referrals in a consistent and sustainable fashion through conditioning users. This is a way to not just survive, but thrive in a world with ever-changing platforms du jour. Done correctly, and for long enough, work here assures you don’t even really need to worry about the changing tides of social and algorithms and can focus mostly on ideas and creative, which is of course the rewarding and meaningful part of knowledge work of all variety.