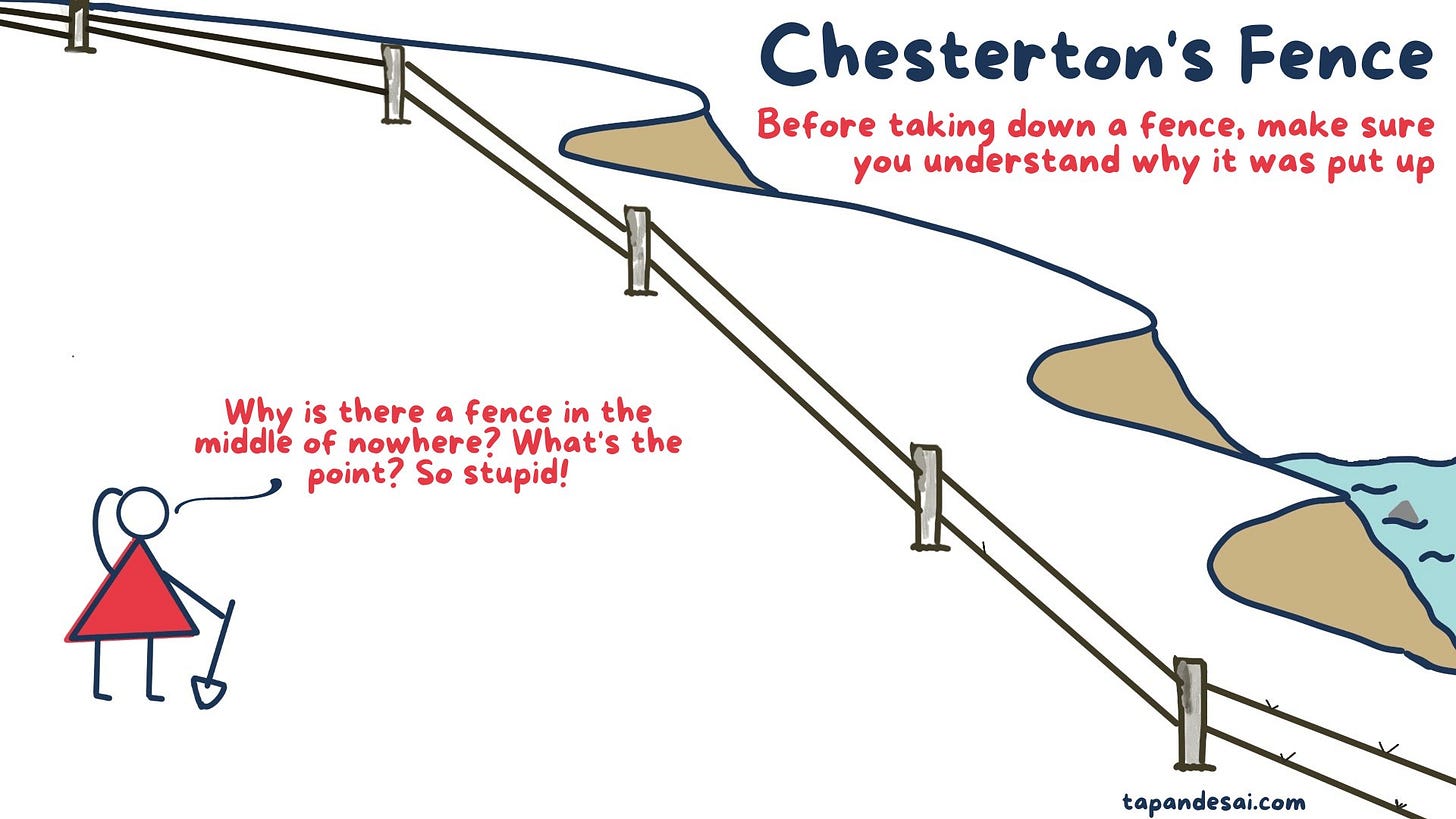

The parable of Chesterton's Fence

A good way to start the year is to actually understand the past before you think you know better

At the edge of a growing city, where glass buildings began to outnumber trees, there stood an old wooden fence. It wasn’t tall. It wasn’t even all that visible. Most days, no one noticed it at all, until one day they did.

The fence ran along a narrow field between a new development and a neglected patch of land. Its boards were uneven, some darkened by age, others replaced long ago with mismatched wood. One day, a group of young planners stood before it, tablets in hand, shaking their heads.

“Why is this even here?” one of them said. “It blocks foot traffic, ruins sightlines, and serves no obvious purpose.”

Another added, “If this city wants to move forward, we need to stop letting outdated things hold us back.”

They drew up plans. The fence would come down. It was seen as “progress.”

An older man, who had lived nearby all his life, overheard them and asked a simple question: “Do you know why this was built?”

They didn’t. They assumed no one did. The fence came down the following week.

For months, nothing happened.

Then the livestock returned. Sheep and cows wandered freely across the field. They trampled seedlings, chewed garden fences, and tore up the soil. Within weeks, the topsoil eroded, paths became impassable, and the young trees planted for the new development died.

Only then did someone find an old map: the fence had been placed decades earlier to keep animals off the slope and protect the soil.

The fence hadn’t been in the way. It had been holding the ground itself together. It turns out the fence wasn’t arbitrary as it had seemed, it had been an answer to a problem solved in the past, but forgotten by the present.

Many people in modernity have a strong instinct: to revolt first and understand later, if at all. But previous generations were not foolish, and it’s more than likely something was setup the way it was for a reason. Traditions, norms, institutions, these look like fences to people born into their benefits but blind to their origins. Marriage, free speech, capitalist market-based systems, even unglamorous things like classroom discipline get dismissed as relics, often by those who have never seen the problems they were designed to solve.

That doesn’t mean fences should never be moved. Some might not be necessary any more. Some protect nothing but inertia or power. The mistake is not in questioning them, it’s in assuming their uselessness before learning their purpose.

Chesterton’s story is not some kind of defense for stagnation, instead it’s a demand we have humility. Before tearing something down, ask what chaos it once restrained. Before replacing it, understand what problem it quietly solved. Otherwise, reform can become an act of blind vandalism against your fellow citizens and make things worse without realizing it. We have countless examples of this all around us.

In the end, the city rebuilt a fence, not the same one, and not in the same way. It was sturdier, better marked, and even paired with proper drainage. Progress returned, but this time it came with memory.

Some fences might exist simply to block movements. Others exist to keep the ground beneath our feet functional. Wisdom is knowing the difference, and modernity’s greatest flaw may be how often it forgets to ask.

Happy New Year, and do not remove a fence until you know why it was put up in the first place. Traditions likely have a reason, even if you had a postmodern professor who insists the past was always wrong.

Oh, you had better believe I’m a proponent of understanding history to put a lens on the present and provide a compass for the future.

In that vein, it’s probably worth introducing your readers to G.K. Chesterton, who used paradoxes and parables to make his points, and gave the world Father Brown (among many other creations). Chesterton’s works are well worth your time.

Chesteron's Fence is a useful framework, but it really captures the conservative viewpoint. There are many cases where it's not worth the effort to figure out why something was done, if the cost of changing it is low. There is a really good analysis of the variety of perspectives on this here (with a bonus bit of history on Chesterton): https://www.hungarianconservative.com/articles/opinion/three-fences-burke-chesterton-change-progressives-conservatives/

It's ironic that the current conservative movement doesn't follow this framework. There was a reason we had a Dept. of Education, a Voting Rights Act and limitations on Presidential power.