All behavior makes sense with sufficient information

When you learn to process the world, you'll see almost no one is crazy

“People aren’t dumb. The world is hard.” — Richard Thaler

Once you internalize a simple truth: that all behavior makes sense with sufficient information, the world looks a lot less crazy (although infinitely more complex). This is actually a much more fun place to be than believing everything is random or never considering basic incentives.

The problem is we rarely have access to the full set of variables driving someone’s decisions. We only see the surface: what they say, how they act, but not the undercurrent of beliefs, fears, and experiences shaping those choices. When we fail to account for this, we label behavior as irrational, selfish, even cruel. Some of it might be. But if we could peer into the hidden machinery of another person’s mind, including the belief systems and ideologies that power someone’s personal human OS, everything usually makes sense (even if it’s misguided).

Understanding this is way more important than being merely an intellectual exercise. It’s a model for navigating the social, financial, and professional realms with insight to make sense of the world and get better outcomes from our teams and users, even have better relationships. Let’s share a few simple examples to crystallize what I’m talking about.

Social situations

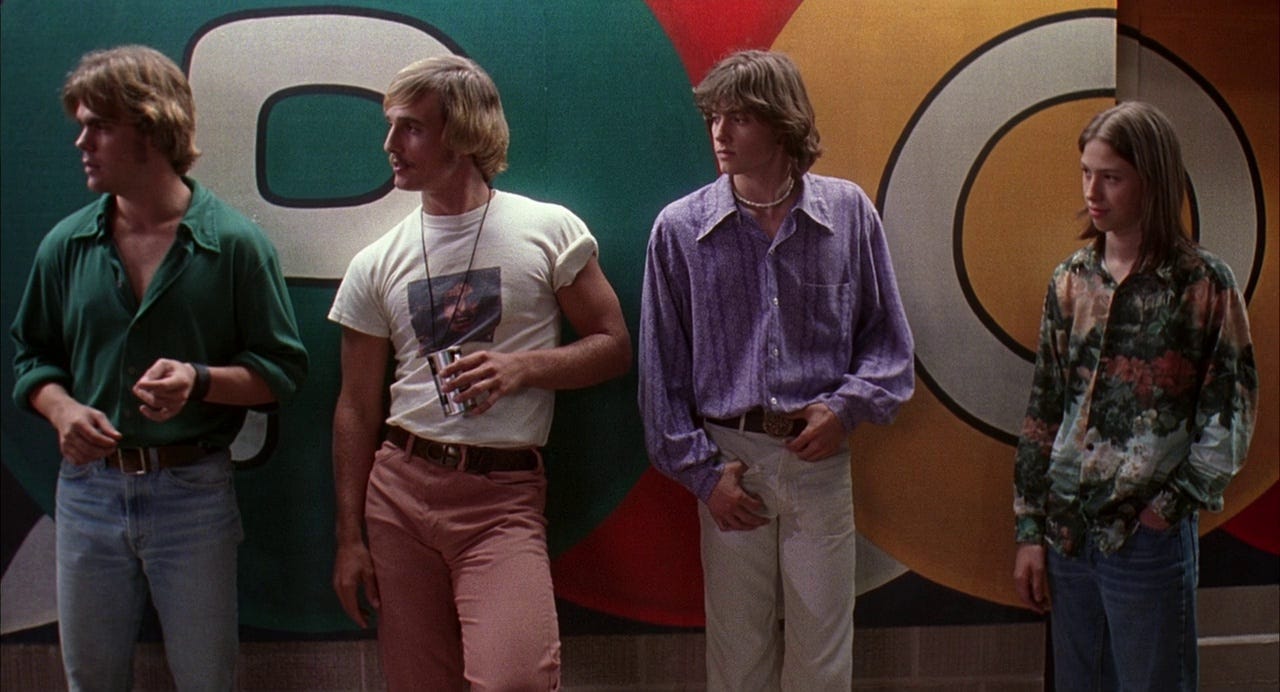

Think about a friend who ghosts your texts, a coworker who avoids team lunches, or a family member who erupts in anger over trivial matters. These behaviors might seem inexplicable, even hurtful. But zoom out and a different picture emerges. That friend who disappears may be battling social anxiety, addiction, or depression. The coworker may fear vulnerability or worry their true self won’t be accepted. The family member could be dealing with unprocessed grief, with anger as their only outlet for expressing pain (if no one helped them learn another way).

In social contexts every interaction is imbued with subtext. Many assume others operate under the same rules they do, but each person carries a unique script shaped by their experiences and values. If we could understand the pressures and histories weighing on those around us, we’d see their actions not as arbitrary but as responses to invisible forces. Their behavior becomes legible, their choices logical within the framework of their lives.

Of note, the NPC meme is really about people who have no personal awareness of their own actions and motivations, let alone the (more complex) ability to parse potential motivations of others.

Financial irrationality

Financial decisions often look like the most fertile ground for irrationality. Why does someone living paycheck to paycheck spend hundreds on designer clothes or go into debt for a flashy car? Why does another refuse to invest or save, even when it’s in their best interest? Yet, these decisions are deeply rational within the context of a person’s life.

For some, spending on luxury items isn’t about the items themselves, it’s about having the smallest sense of control or dignity in a world in which they feel powerless. For others, saving might feel futile because past experience has repeatedly taught them long-term planning is a luxury they can’t afford. When you dig deeper, these choices are less about numbers and more about emotional survival. Financial behavior, no matter how counterintuitive, follows its own internal logic when viewed through the right lens.

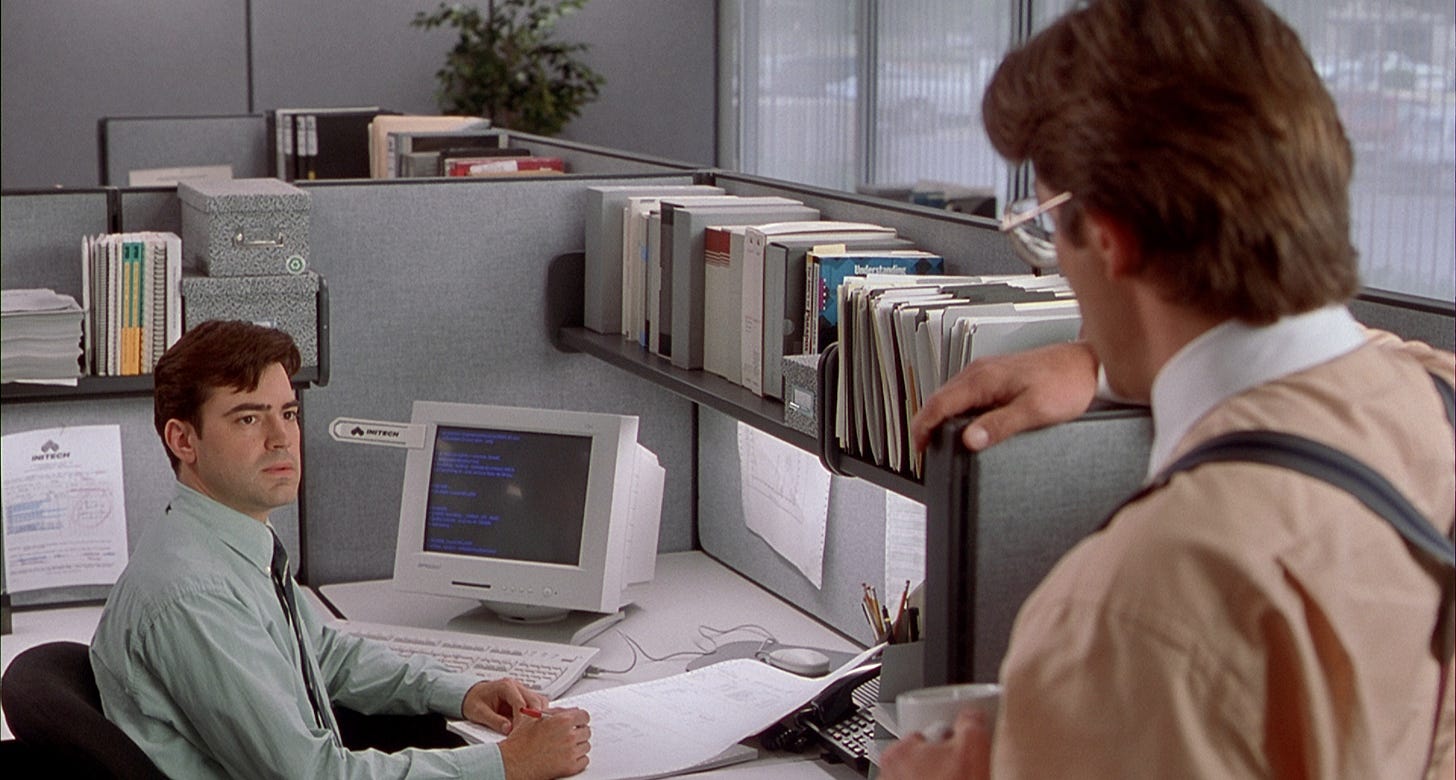

Professional life

In the workplace, certain behavior can seem irrational. Why does a colleague constantly seek validation? Why does your manager fixate on minor details while ignoring larger issues? Professional environments are ripe with behaviors that appear irrational until you understand the unspoken incentives and fears at play.

Your colleague’s need for praise might stem from years of being undervalued in past roles, making each ‘good job’ a small but necessary assurance of their worth. Your boss’s micromanagement could be less about control and more about a deep-seated fear of failure, believing every tiny oversight could spiral into catastrophe. In professional settings, people often perform roles dictated by invisible scripts written by past successes, failures, and the expectations of those above and around them.

With enough information, even the most frustrating workplace behaviors become at the least understandable. They aren’t the result of someone purposefully being difficult but of careful, if subconscious, calculations aimed at survival and success in a competitive ecosystem.

Competitive arenas

Poker is a game of imperfect information. Each action whether a bet, call, raise or fold reveals something and conceals something else. To the untrained eye watching poker on TV, a player who goes all-in on a weak hand might seem reckless, even foolish. But in poker, every move carries a calculated attempt to manipulate perception and maximize chances of success. The bluff, often misunderstood as pure deceit, is actually an act of storytelling: persuading an opponent that your hand is unbeatable.

Probably the most powerful example from poker on behavior is the concept of ‘going on tilt,’ wherein a player spirals into irrational aggression after a bad beat. To outsiders, it might appear like raw emotional implosion, but there’s a deeper subconscious rationale at play. The player is reacting not just to the lost hand but to the cumulative pressure of the game, the weight of prior losses, or belief that changing their gameplay aggressively might break an opponent’s rhythm. Tilt makes sense when you understand it as an emotional recalibration in a high-stakes environment. I’ve personally seen cases where going on tilt was precisely what was required for a player to win a tournament. This doesn’t always work out, of course.

Even the seemingly inscrutable tight player who folds hand after hand has their own logic. They are carefully curating their table image, waiting for the perfect moment to exploit a cultivated perception. They know each opponent is operating under a unique matrix of probabilities, personal history, and psychological tactics, and they’re using this acute awareness to their advantage.

Poker is a great microcosm of life: a game where all behavior makes sense if you have sufficient information. Every move reflects a balance of risk, reward, and the stories we tell ourselves (and others) about what might be hiding in the cards.

Quick wrap…

Understanding all behavior makes sense with sufficient information transforms how we view others. It challenges us to move beyond snap judgments and approach things with curiosity. Instead of asking, ‘why are they acting like this’ we can try, ‘what might I not know about their world?’ The answer is always there: a web of experiences and motivations that, if uncovered, can bridge the gap between confusion and understanding.

A lovely article, but I take slight umbrage at poker as a metaphor for life. It is exactly the opposite.

Poker has fixed rules and finite outcomes with knowable probabilities. It is a zero sum game where to win someone has to lose.

Neither of these is an accurate reflection of life except for that of the sociopath and the scoundrel.

Life is perfectly complex, and our inability to capture it in probabilities is what creates opportunity and everything that is worthwhile. A life that has been so constrained as a poker game is a prison.

The behaviors in poker should not be lauded. They are manipulations and discreditable. They are also inevitable in a zero sum game. In a pure poker game, winning and losing would become as probability as a roulette wheel. That is why bad behavior - lying, misrepresentation, and loutishness - become virtues: there is no other escape, you have to “cheat” to win.

In real life, none of that should be necessary. It is only so because those with power attempt to constrain the rules to the point where there is either no fair way to win or they always win (clientism, oligarchy and the mob).

Life is beautiful and complex and not poker.

To paraphrase Morgan Housel, your personal experiences make up maybe 0.00000001% of what's happened in the world, but maybe 80% of how you think the world works.